“Sad Grownups” Explores What Sadness Says About Life

Table of contents

Rechercher dans ce blog

- février 20266

- janvier 202614

- décembre 202510

- novembre 20259

- octobre 202515

- septembre 202518

- août 202516

- juillet 202519

- juin 202515

- mai 202519

- avril 202515

- mars 202518

- février 202515

- janvier 202511

- décembre 202412

- novembre 202414

- octobre 202419

- septembre 202419

- août 202415

- juillet 202419

- juin 202418

- mai 202417

- avril 202418

- mars 202421

- février 202417

- janvier 202412

- décembre 202314

- novembre 202315

- octobre 202319

- septembre 202318

- août 202318

- juillet 202314

- juin 202317

- mai 202317

- avril 202311

Qui êtes-vous ?

The Best Southern Books of February 2026

Recent in Technology

Feeding the Ghosts: Ancestral Offerings and New Growth

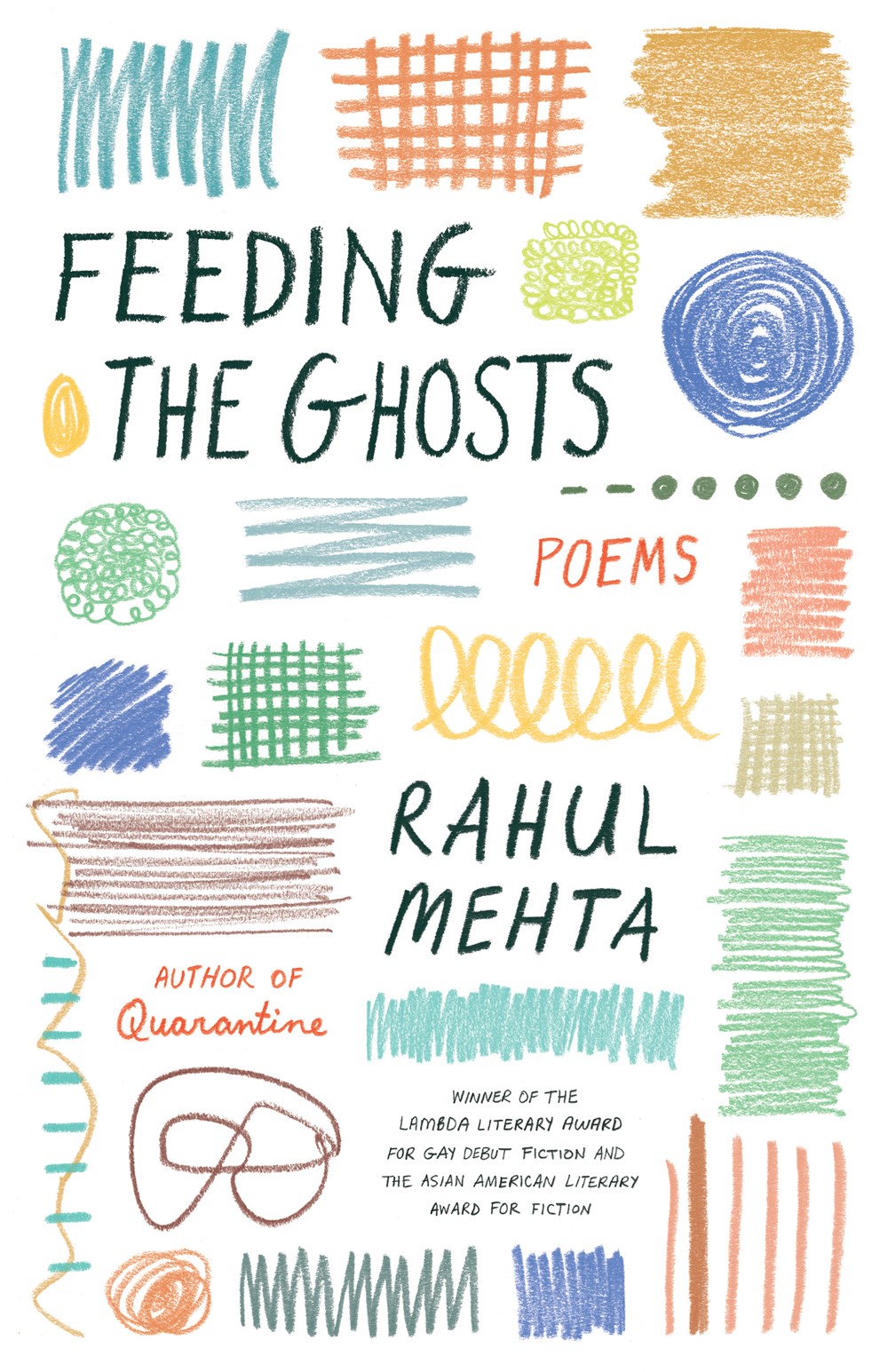

Rahul Mehta’s Feeding the Ghosts is a reflective and at times melancholic collection that offers a fresh perspective on how to maintain identity in the shadows of family and discrimination. The poems are honest, heartfelt, and easily accessible. Fans of Rahul Mehta’s previous novel and short story collection will appreciate the often conversational and prose-like nature of these poems. However, the importance of this collection lies in the voice it gives to the intersectionality of a gender nonconforming Indian American raised in West Virginia. In these deeply personal poems, Mehta manages to reveal parts of their lived experience while pulling a gold thread of truth and beauty from each.

In the opening poem, “Swords,” the speaker promises “to tell myself my own life story,” an expectation that is fulfilled in subsequent poems. This is followed by the deeply personal poem “Pen,” where the speaker begins with close observation to tell a story of their father, an immigrant, who writes,

on that impossibly

thin paper the blue of

the sky the day after

a storm, in Devanagari

script that rises and

falls and crashes

like waves—

an aerogram

home.

The speaker imagines wielding the father’s tools to craft their own life in this new home, while holding the understanding that their father is still rooted to another continent and another way of thinking and being in the world. The pen and writing as a balm continue as a metaphor throughout this collection as a means of having a voice in one’s own identity. Many of the poems embrace “un-forgetting” and reclaiming the past as a means of moving forward. There are offerings to ancestors, as a way of feeding the ghosts, but also as a way of letting go of the past, “to let grow something new.”

The importance of heritage and the sensation of being pulled between two continents returns in “Laundry Day” as a pink kurta, a collarless tunic, “hangs / from a hook on my fire escape…The breeze breathes / into it / life.” This image stirs up memories of family members, some who still live in India “teaching me past, present & future,” others who got “lost among racks of / plaid flannel shirts / at a JCPenney.” When the first-generation speaker visits South India “where two rivers clash,” readers experience the collision of two cultures. It ends with the speaker teaching writing in Philadelphia, “the sounds of / our stories / rising.”

One of the anchor poems in this collection, “Tunnels,” questions the assumptions we make about others by opening with an overheard conversation between two privileged white women discussing the unhoused population. The speaker then turns the magnifying lens inward, questioning their own preconceived notions, and trying on different versions of themself at the department store, which is its own acknowledged privilege. Ultimately, the speaker rejects these versions to honor their values and admires how tunnels, the same tunnels that provide relief to the unhoused population, “bridge distances, connect people and places that are close but far away.” This poem explores privilege in a way that does not provide answers but offers a method of self-exploration that opens possibilities for readers to do the same.

The strong emotional drive to obtain parental approval, even as it clashes with one’s own identity, is explored in “The Secret.” The father asks, “though he knew Robert and I / were a couple, was, in fact, / fresh with this knowledge—/ Which bedroom is yours?’’ And in later poems, “I too know the weight of making immigrant parents proud,” and “…punishing myself is my religion, and it is hard to unravel what has been stitched into your genes by your ancestors’ trembling fingers.”

As part of this process of claiming one’s own identity, there are poems where the speaker employs careful observation of nature in order to find answers realizing,

the snowdrops’ heads are bowed

in prayer. and beneath the

tulip poplar the crocuses

are cleaning their throats

to sing their hymn

of coming spring.

i don’t have to do a thing

to make this happen.

rain will fall, wild-

flowers will bloom.

i don’t have to do a thing

to make this happen.

Poems such as this one are written in the practice of attention that was Mary Oliver’s signature and the series of “Morning Prayer” poems call to mind Louise Glück’s “Matins.”

Mehta’s use of metaphor, narrative, juxtaposition, and observation are powerful, and this collection relies on previous strengths developed in prose. “Ghazal” is one of the best poems in the collection, making readers wish for more formal impulses. It contrasts the love and shame the speaker felt as a child for their grandmother who didn’t fit in to white America. It grapples with trespasses and boundaries, the petals and roses taken “from our neighbors” to be sewn into “fresh garlands…of marigolds and rose” for her “deities in careful rows.” The speaker reaches back in time to offer their “scared, younger self…a white rose.” This peace offering, both to the memory of the grandmother and to the younger self, does not sugarcoat the reality, “Aware, as well, the dangers of trespassing while brown / In ‘post-racial America’ (ha!), my glasses are not tinted rose.”

Feeding the Ghosts is remarkable for the way it explores issues of discrimination in the US today and the impact of what we carry from our families. It never assigns blame, rather, it acknowledges these truths from lived experience and holds them to the light. One of Mehta’s signatures is braiding honesty, resilience, and that gold strand of beauty into their work. These poems acknowledge that life is flush with “currents above and current below. / something is always happening / you cannot see.”

POETRY

Feeding the Ghosts

By Rahul Mehta

The University Press of Kentucky

Published March 5, 2024

People

Most Popular

Table of contents

Mezghebe’s Debut: Just “What You’re Looking For”

Tags

Categories

Ad Code

Popular Post

“Sad Grownups” Explores What Sadness Says About Life

Table of contents

Labels

Popular Posts

0 Commentaires