“Sad Grownups” Explores What Sadness Says About Life

Table of contents

Rechercher dans ce blog

- février 20265

- janvier 202614

- décembre 202510

- novembre 20259

- octobre 202515

- septembre 202518

- août 202516

- juillet 202519

- juin 202515

- mai 202519

- avril 202515

- mars 202518

- février 202515

- janvier 202511

- décembre 202412

- novembre 202414

- octobre 202419

- septembre 202419

- août 202415

- juillet 202419

- juin 202418

- mai 202417

- avril 202418

- mars 202421

- février 202417

- janvier 202412

- décembre 202314

- novembre 202315

- octobre 202319

- septembre 202318

- août 202318

- juillet 202314

- juin 202317

- mai 202317

- avril 202311

Qui êtes-vous ?

Tupac Shakur, By Those Who Knew Him

Recent in Technology

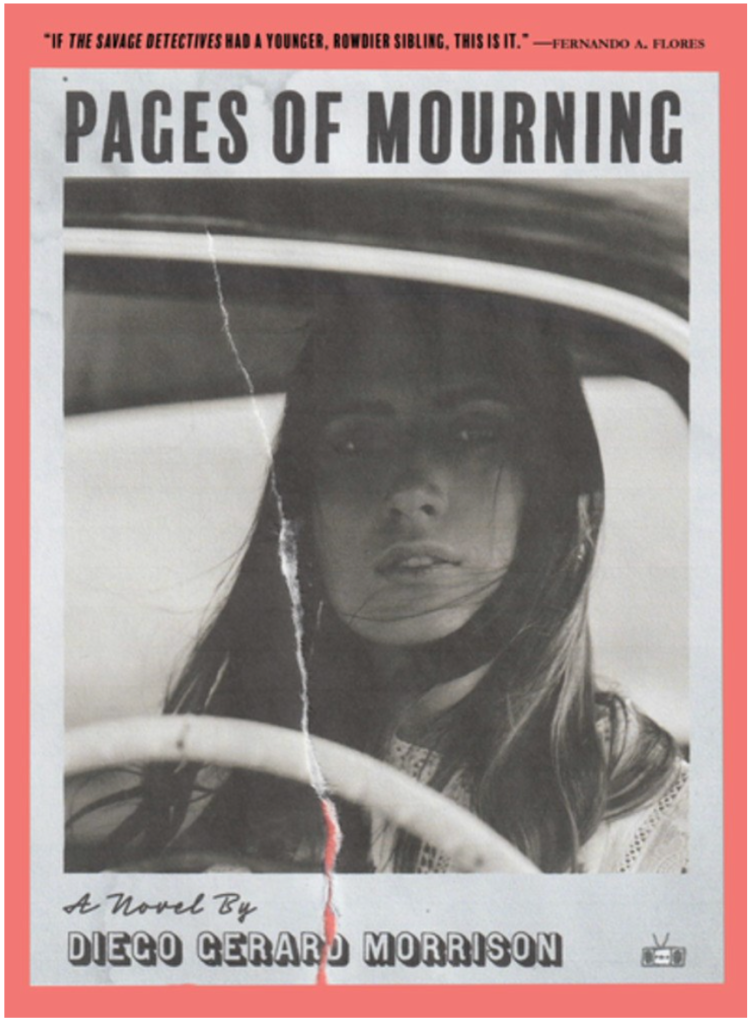

Magical Realism in the “Pages of Mourning” by Diego Gerard Morrison

Diego Gerard Morrison’s second novel, Pages of Mourning, may call Mexico its main

home, but its first scene is a literal writer’s nightmare in a New York City coffee shop. Aureliano Más, the novel’s rarely sober, often haunted, and slyly named protagonist, sees dead people. It happens when he’s asleep and even, sometimes, when he’s awake and drunk out of his mind. This time, it’s a daydream of his recently deceased friend Chris, an editor at a prestigious publishing house. “Daydream-Chris” has too much fun poking at a manuscript of Aureliano’s novel-in-progress, No Magic in Realism, a text which “wants to make Magical Realism shatter.” He’s ready to tell Aureliano why his novel doesn’t succeed, and he’s not afraid to go into painful detail.

Novels-within-novels notwithstanding, Morrison may have shattered Magical Realism

already, or at least cracked its dusty looking glass. But he doesn’t do it by reacting against its typical tropes. Instead, he reexamines the usual suspects: cyclical narratives, ghosts among the living, and impossible coincidences included. His novel extends from the 1970s to 2017 and finds its primary locales in Mexico and New York. While Aureliano’s difficulties supply its main center of gravity, the narrative pivots through different perspectives. An incomplete novel by his Aunt Rose and a tequila-induced remembrance by his father, Aureliano Más the First, provide alternate viewpoints to Aureliano’s own.

From the start, one of the more charming elements of Morrison’s literary novel is the step

it takes beyond mere self-awareness. It’s more like a hall of mirrors, reflections of reflections continuing into infinity. We encounter references to heavyweights like 100 Years of Solitude, Pedro Páramo, Under the Volcano, and The Crying of Lot 49, to name the big ones. The novel even has its own Bolaño bent of being writing about a writer trying to write. Still, these references aren’t there just for the name-dropping. From a certain angle, Pages of Mourning is a delightful and ambiguous pastiche of them all. We have the drunken despair of Lowry, the playful ghosts of Rulfo, the synchronicity of Garciá Márquez, and the restless search of Pynchon, all in one homey, if crowded, living room.

Morrison’s measured but expansive prose paints a moving picture of how artists use the

supposed alchemy of the creative process to confront grief. Is it magic? Bullshit? We’re often left with the impression that the truth exists somewhere between two poles: writing as healing fantasy and writing as poisonous narcissism. If we fret too much about the questions, we can at least enjoy Morrison’s captivating power of description, as in an early passage depicting Mexico City:

The sun has burned off the early cloud-cover and the sky beams a clear blue that defies

all sense of realism. The streets are riddled with car exhaust, busted plumbing fumes, street-stall smoke. All those tedious molecular assailants that glue the corners of my eyes, that itch on my skin, that turn my mouth to a swamp, enough to make me wish I could really teleport back to the winter of New York.

Morrison’s narrative style shows both “certain death” and the “endless possibilities of

life” in constant interplay. In the middle of it all, living is the only thing Aureliano seems capable of doing. Even then, he flounders. He certainly can’t write, not even when his aunt Rose, a successful writer herself, has hooked him up with living quarters and free time via the prestigious Under the Volcano fellowship, a program for budding novelists. What’s worse, he’s surrounded by the ultimate artistic torture: successful peers. Nayeli, his designated fellowship mentor, is that rare bird, a wealthy writer with political savvy and literary accolades. She’s well into her much-anticipated new novel, Drug War Aspalis, a surefire hit about the very real Iguala mass kidnapping of 2014. His two other fellowship cohorts, whom he labels “Mexican Tom Waits” and “the Emo,” are also much farther along in their novels, which they demo at crowded readings to roaring acclaim.

To make things even worse, everyone in Aureliano’s life, minus one good-natured

bartender/ barista, seems to dislike him or, at the very least, resent his choices. At best, this distaste softens into pity, and that’s only for circumstantial reasons. His life hasn’t been easy. Throughout Pages of Mourning, it doesn’t get easier. His mother, Édipa Más, skipped out on him early. His friend Chris committed suicide. Aureliano’s quest to find closure around these two deaths supplies the novel with its main momentum. For Chris, it’s a straightforward but difficult climb. He understands he didn’t mourn his friend at all. Instead, he let his ghost loose into a sickened interior life, free to mock him endlessly. His mother is the real trouble. “With [Chris],” Aureliano says, “at least there is a body.” He’s not even sure if his mother’s dead. The last time anyone saw her, she was running away, leaving her family behind, as her mother had done before her. Aureliano’s battle against writer’s block merges with his investigation into her disappearance. He visits his father’s cannabis-turned-coffee operation in, of all places, Comala. He peruses Rose’s Snake Skin: Brief Passages in the Life of Édipa Más with little success. The whole time, death and its discontents appear to Aureliano at every turn, but few of the living seem to care. Whether rampant alcoholism colors his perception remains to be seen.

As with Morrison’s first novel, Myth of Pterygium, it’s the case of a brink-of-failure artist

against the world. It seems to be the recurring void at the core of both works, though Pages of Mourning tempers down the near-future absurdity of Pterygium while still holding the same brutal heart and quiet humor. In the end, whether art does anybody good may be an irrelevant question. We still have death. We still have grief. At the very least in Pages of Mourning, the dead we have, we bury. The ones we can’t, we let go.

Pages of Mourning

Diego Gerard Morrison

Two Dollar Radio

Published May 14, 2024

People

Most Popular

“Ballot”: The Stakes of American Voting Are Higher Than We Think

Tags

Categories

Ad Code

Popular Post

“Sad Grownups” Explores What Sadness Says About Life

0 Commentaires