“Sad Grownups” Explores What Sadness Says About Life

Rechercher dans ce blog

- janvier 20263

- décembre 202510

- novembre 20259

- octobre 202515

- septembre 202518

- août 202516

- juillet 202519

- juin 202515

- mai 202519

- avril 202515

- mars 202518

- février 202515

- janvier 202511

- décembre 202412

- novembre 202414

- octobre 202419

- septembre 202419

- août 202415

- juillet 202419

- juin 202418

- mai 202417

- avril 202418

- mars 202421

- février 202417

- janvier 202412

- décembre 202314

- novembre 202315

- octobre 202319

- septembre 202318

- août 202318

- juillet 202314

- juin 202317

- mai 202317

- avril 202311

Qui êtes-vous ?

Recent in Technology

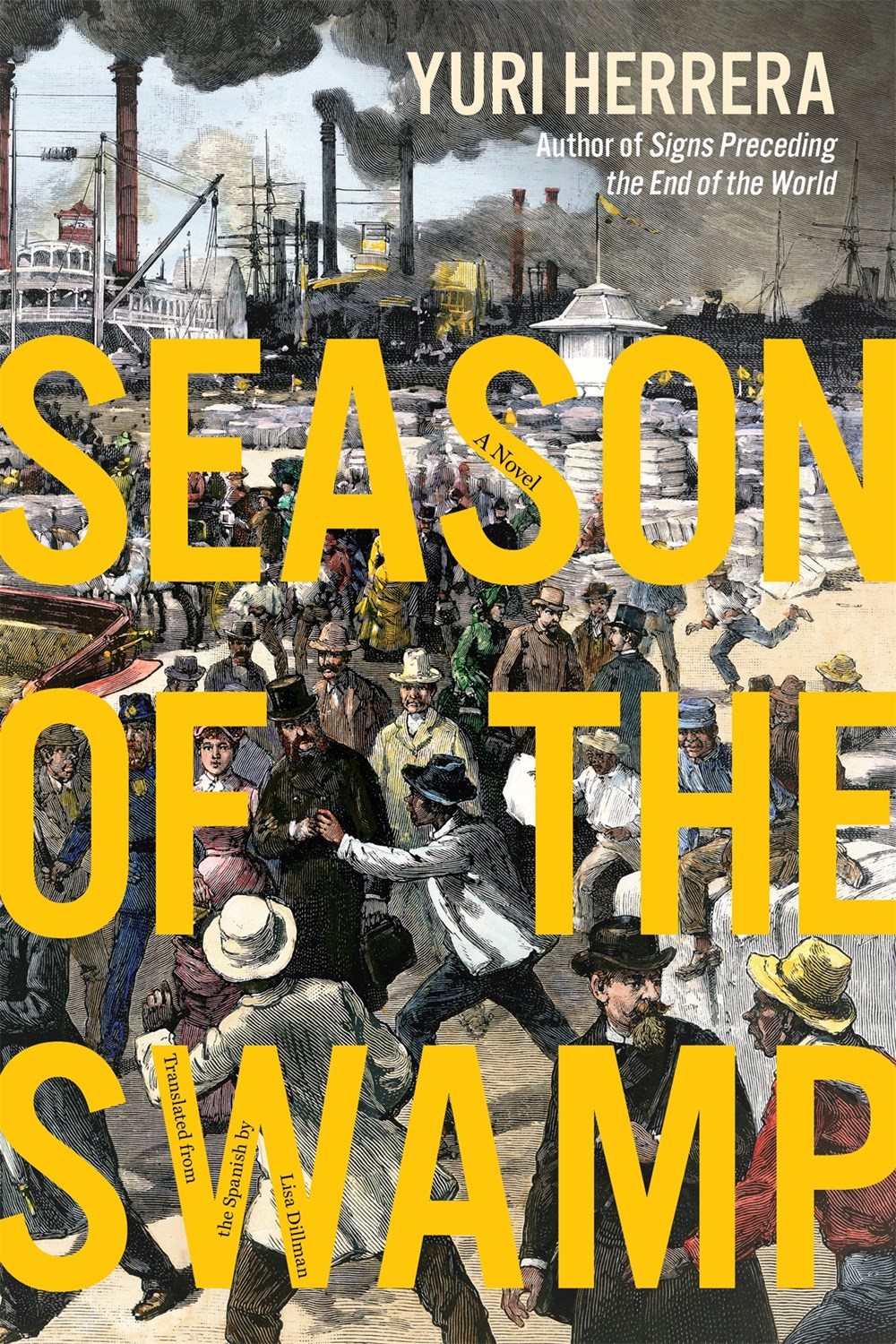

“Swamp”: An Historical Novel Full of Symbolism, Metaphor

Yuri Herrera’s Season of the Swamp (translated from Spanish by Lisa Dillman) is historical fiction that transports readers to pre-Civil War New Orleans. Through the eyes of Benito Juárez, revolutionary and first president of Mexico, we are shown how the fires, fights, and plagues of New Orleans created an uncivilized backdrop for Juárez to plan his triumphant return from exile and to begin his much more elegant upheaval in his home country. This could easily be shelved alongside The American Daughters by Maurice Carlos Ruffin for the way it gives us another seam to pull on New Orleans so we can see how it came to be sewn together.

Herrera is quick to point out the hypocrisy and inequality upon arrival in 1853 New Orleans. Shortly after finding a home base, Juárez is taught the differences between freed men of color, Creoles, and enslaved people who are “captured by birth.” “It’s quite complicated,” their friend the printmaker tells them, noting that “so long as they’re white they can marry, own property, file lawsuits, et cetera; and then there’s everybody else.” Racism and colorism intersect with Juárez’s exile status, along with his difference of language, to create a liminal space for his group of radical rebels to exist in within the city. He is not white enough to obtain the type of work that could send money home to family in Mexico, and almost not enough to survive. But he is also not Black enough to have Twigs, the enslaved hunter, to harass him at the coffeeshops where his revolt is being plotted. It is from this alienated identity that Herrera gives an impressively honest account of this city at that time.

Madame Doubard, Herrera’s sassy French heroine, gives history of how New Orleans came to be: “And this city began with sick people, prostitutes, thieves, drunks. France sent over whatever they didn’t want. That was long ago, but some of us learned the habit of not being ashamed of that, of being detritus.” From these people, Herrara depicts a city at war with itself. Law means little (unless you are a person of color, of course). When law won’t suffice, violence settles disputes. Fires consume orphanages and businesses with little concern for how they started. And Herrera’s depiction of New Orleans’ summer is one of the best I’ve ever read: “The real hot arrives slowly but not subtly, and by the time you can say its name it’s already named itself, littering the street with sunstroked folk.” Set against this backdrop, Herrera navigates Juárez through bear fights, murders, infatuation, and even Juárez’s own experience of “Yellow Jack” (yellow fever). Herrera even brings revolution to New Orleans – its residents just as ready for change as Juárez:

We need to burn it all down. We need to haul out, said someone else. Ha, and go where? Up north, or to Mexico, We’re not going anywhere, we’re staying right here to beat them at their own game, using their rules. That makes no sense, the rules were made for them to win. But we’re already winning in a way, aren’t we? I mean, here we are, thinking aloud.

Like much of the best literature, Herrera fills the pages with symbolism and metaphor. A compass is lost at the beginning of the story. It is given to Juárez as he readies to disembark back to Mexico where he will create a new country. In New Orleans, Juárez’s direction is taken from him but through his friendships and tribulations he finds his way home. The sought for glyph of a bird walking away while looking back embodied Juárez and his compatriots. Juárez’s fever dreams reveal as much about plans of creating a home built of thought and rationality as much as they do his delirium. Even the alligator foot gifted to him by the native Houma man seems to speak of the adaptability and rebirth the animal tends to represent.

Like a great artist, Herrera found a story within a larger work and made its color shine so that the whole of the masterpiece – in this case, New Orleans – draws us in deeper. If there is something negative to say about this work, it is that it is too short. While Herrera has captured the spirit of a place many attempt to manifest and fail, 160 pages felt too short a stint in this wild world where revolutions are reasonable and drinking coffee amongst friends is an act of treason. But I suppose that for Herrera, and Benito Juárez, a season in this swamp is all it takes to make something big happen.

FICTION

Season of the Swamp

By Yuri Herrera

Graywolf Press

Published October 1, 2024

0 Commentaires